Amazon • Bookshop • Barnes & Noble • Waterstones • Palermo • Interview

The Middle Ages still have a few things to teach us. Here are 464 pages of real medieval history served with just a few morsels of dogmatism — the dogmatism of tolerance. Meet the peoples… And join the ranks of the cognoscenti!

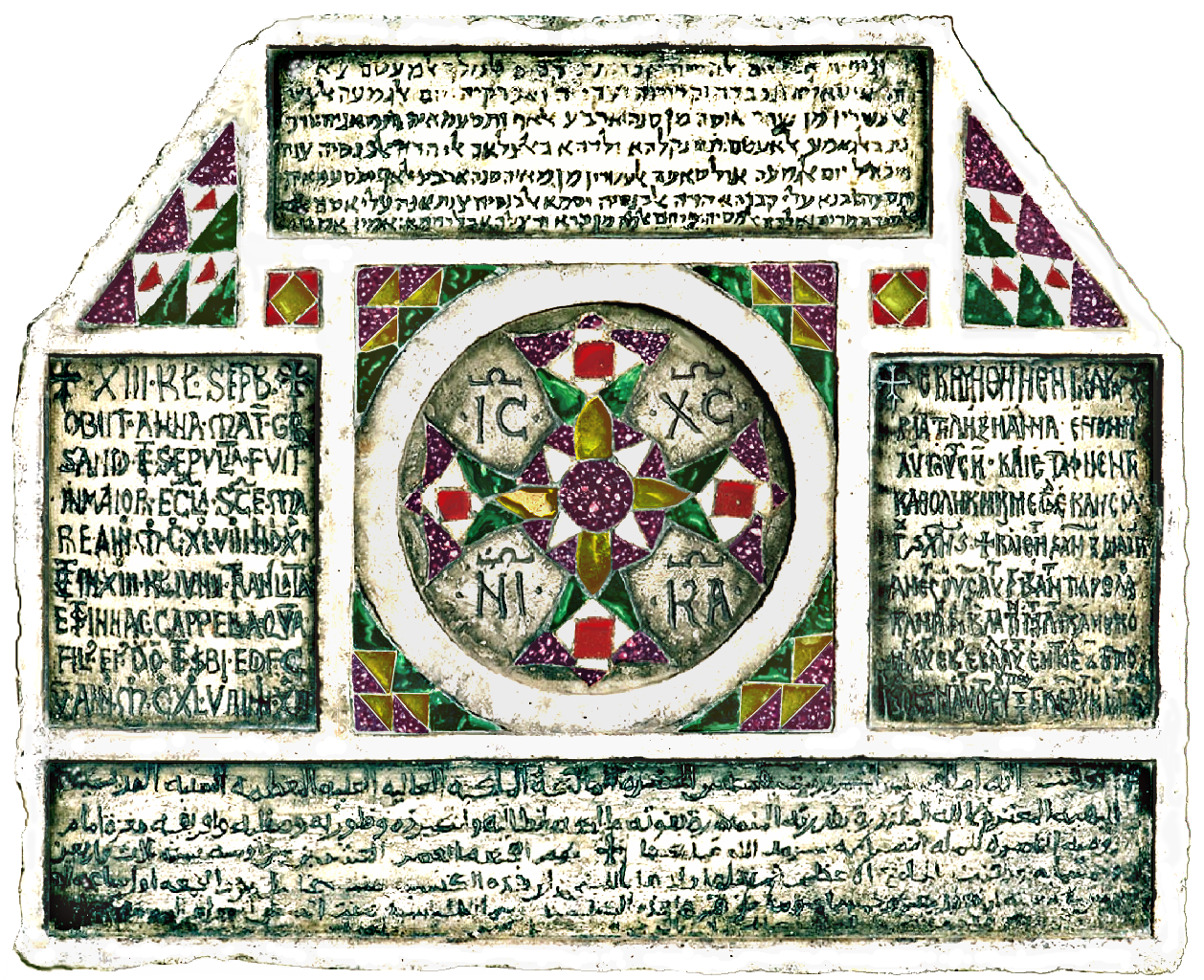

Multilingual tombstone of 1148 inscribed in Greek, Latin, Arabic, and Judeo-Arabic similar to Hebrew

Can the eclectic history of the world's most conquered island be a lesson for our times? Home to Normans, Greeks, Arabs, Germans and Jews, it was for centuries a crossroads of cultures, faiths and learning — the epitome of diversity. Here one of Sicily's leading historians introduces the place where Europe, Asia and Africa met, where bilingualism was the norm, divorce was legal, the rights of women were defended, and the environment was protected. All before 1250.

Kings like Roger II, whose legal code of 1140 famously referred to "the diversity of our people," welcomed foreign luminaries at court in what emerged as one of the most prosperous states in Europe, encompassing the island of Sicily and most of the Italian peninsula south of Rome. Queens like Roger's daughter, Constance, and daughter-in-law, Margaret, emerged as the strongest female rulers in the medieval Mediterranean, governing a multiconfessional society of Muslims, Jews, and the Christians of the Byzantine East and Latin West.

The story of medieval Sicily welcomes us a into a wider world. Paper making arrived from China and Hindu-Arabic numerals from India.

This book presents a survey of the ancient and medieval civilization(s) of Sicily. Sicanians, Sikels and Elymians, Greeks, Phoenicians, Carthaginians and Romans, followed by the Vandals and Goths, the Byzantines, Amazighs, Fatimids, Normans, Swabians and others. Chapters are dedicated to cuisine (with recipes), religions and languages. Ethnogenesis, phylogeography (genetics), law, Sicilianistics, Sicilianità and feminism are considered. There are 22 pages of maps and charts, plus 11 genealogical tables, and numerous photographs of regalia, charters and places. There are descriptions of sites such as Monreale's abbey and the palatine chapel of Palermo's Norman Palace, with their syncretic Norman-Arab-Byzantine architecture.

Since publication of its first edition in 2014, this informative work has become a cornerstone in the international study of Sicilian history, popular among general readers even while it is used as a text in university courses. The peer-reviewed second edition is enlarged, reflecting recent research by leading scholars. There are endnotes, an appendix listing original sources, and (at 25 pages) the lengthiest timeline of Sicily's history to ever see print.

Can a book change our ideas about the way we view our world? This one just might.

Available from Amazon, Bookshop, Waterstones and other vendors. In Sicily exclusively from Libreria del Corso at Via Vittorio Emanuele 332 in central Palermo. Listen to an interview with the author on the The Italian American Podcast.

The foreword, preface, table of contents and acknowledgments of the second edition (published in 2024) follow.

FOREWORD TO THE SECOND EDITION

"What unites us is far greater than what divides us," declared King Charles III, then Prince of Wales, at London's Banqueting House, in Whitehall, on June fifteenth of 2000 on the occasion of the opening reception for his joint art exhibit with Prince Khalid al-Faisal of Saudi Arabia. Having played a (very) small part in promoting the exhibit, "Painting and Patronage," which involved the sale of the two princes' paintings for charity, I was struck by the great diversity of the many hundreds of attendees, for while the future king's words were not altogether original, the event certainly was. At one end of the hall, as if to remind us that the paintings were inspired by the picturesque Asir region, was a huge Arab tent evoking Bedouin tradition. Among royals attending were King Constantine of Greece and at least a few whom I already knew, namely Prince Ermias Sahle Selassie of Ethiopia, Prince Carlo de Bourbon of the Two Sicilies, and Prince Emanuele Filiberto of Savoy.

The uncommon event was a reminder that ethnicities and cultures, however different from each other, sometimes find common ground. We might not always worship together, but we can still walk together. That is largely the story of medieval Sicily for about three centuries.

The first edition of this book saw print early in 2014. Though intended for a general "trade" readership, it has become popular with cognoscenti and scholars as an introduction to the subject, presenting an object lesson in the nature of early multicultural, or co-cultural, societies, as well as being a concise "foundational" history of the world's most conquered island. The book's popularity, even among professors, is owed largely to the fact that it brought together, and connected, a number of topics rarely presented very cohesively in one volume even in edited collections (anthologies) written by a team of authors. Moreover, being written by Sicilian scholars based in Sicily, it reflected a certain authorial view more insightful than those presented in books written in the Anglosphere by foreigners.

Reflecting living history, this second edition is revised through a greater elucidation of certain topics, and with the addition of a number of photos, maps and charts. It sees the clarification of a few historical details and the removal of misleading or ambiguous passages. An entire chapter is dedicated to cuisine, its polycultural lineage considered along with a few medieval recipes. Several sections are, in part, extracted from Kingdom of Sicily 1130-1266 (published in 2023), notably the chapters on cuisine, Monreale and the Sicilian language, and some material in the Sources. The text and translation of the Contrasto of Cielo of Alcamo have been added. There are a few endnotes, particularly for arcane details not covered at length by the books in the Reading List. Some of these features have been requested by readers over the years, and they are included for the benefit of those seeking more information.

Fine scholars who have contributed something of note to this edition are mentioned in the Acknowledgments. Their contributions, which improved this work, are greatly appreciated. The Preface and Introduction are largely untouched, and an effort has been made to retain the greater part of the narrative text. A few subtle changes reflect an attempt at greater accuracy but also consideration for ethnic identity; the gentilic Amazigh, sometimes Imazighen, being an autonym, substitutes the more Eurocentric Berber.

Fine scholars who have contributed something of note to this edition are mentioned in the Acknowledgments. Their contributions, which improved this work, are greatly appreciated. The Preface and Introduction are largely untouched, and an effort has been made to retain the greater part of the narrative text. A few subtle changes reflect an attempt at greater accuracy but also consideration for ethnic identity; the gentilic Amazigh, sometimes Imazighen, being an autonym, substitutes the more Eurocentric Berber.

The Reading List has been revised to include a number of books, including a few of my own and those of Jacqueline Alio (shown with me in this photograph), who contributed to the first edition of this work by offering a female historian's view, specifically in the chapters about women. Indeed, The Peoples of Sicily was the first book written about our island's history in English by a male-female authorial couple.

This volume represents an approach to scholarship that has been termed autohistory, defined in Chapter 30. In many cases, a historian chooses a subject; in other instances, such as this one, the subject chooses the historian. For the author of this work, being a historian dedicated to southern Italy is not simply what he is but who he is. "I definitely think one’s background helps to determine how to approach one’s subject," noted David Abulafia. "In my case the Sephardim and the Mediterranean."

This contrasts sharply with the approach taken by most foreign (non-Italian) scholars, however competent, writing xenocentrically in English. The advantage for you, the reader, is that, unlike the mass of works written by foreigners, books such as this one clearly connect Sicily's past to its present. Reflecting autohistory written in Sicily, the narrative in the following pages sometimes refers to we and here rather than they and there.

This is not a work of modern history. The greater part of the history covered in these pages occurred before 1500, and its focal point is the Kingdom of Sicily, the Regnum Siciliae, founded in 1130. However, it has been necessary to dispel a few misperceptions about Sicilian history spawned after the Middle Ages. Rather than "revisionism," this volume, like its earlier edition, seeks to clearly present certain facts and perspectives often overlooked or minimized in the cascade of pedantic analysis and creative theory typical of academic monographs. However, it is not the intent of the author to critique the work of fellow scholars.

Over the years, The Peoples of Sicily has been used as a text in a number of university courses, particularly for undergraduates in their final years of study, and in continuing education. It has also been cited in dissertations and academic monographs. Though the book you are reading is not, strictly speaking, a purely scholarly work, it benefits from recent academic research. The reader seeking more thorough citations and source information is referred to other books, such as Kingdom of Sicily 1130-1266 at 900 pages, and those of Jacqueline Alio, notably her Queens of Sicily 1061-1266, at 740 pages.

History offers us much-needed context and perspective about our world and our complex times.

— Louis Mendola

Panormus, Regnum Siciliae

Martius MMXXIV - Shaban 1445 - Adar Alef 5784

PREFACE

"If we cannot end our differences, at least we can help make the world safe for diversity."

— John Fitzgerald Kennedy

Monochrome is boring. Our world is much more than a single color. At Palermo's Zisa, a royal palace built during the twelfth century in the eclectic Norman-Arab style, is displayed a tombstone created in Byzantine polychrome inlay (shown here) commemorating a certain Anna, a Norman wife and mother who died in 1148. Bearing inscriptions in Latin, Greek, Arabic and a peculiar Judeo-Arabic similar to Hebrew, it survives as a tangible legacy of what, in its time, was the world's only truly multicultural, or co-cultural, society, a convergence not only of peoples but of ideas.

Here, on this island variously claimed by Europeans, Africans and Asians, are the foundations of a lesson for our times. For all time. In Sicily, for two centuries, from around 1060 to 1260, people of diverse cultures, faiths and lifestyles lived together in something approaching harmony. Theirs was a polyglot society virtually untainted by the bigotries of religion, devoid of oppression based on gender or ethnicity. Sadly, it was not to survive the thirteenth century.

Not that it was ever perfect, or even very novel. Ancient Rome, to cite but a single prior example, was a center of immigration from a sprawling empire and its far-flung provinces, with Roman citizenship acquired on an equal basis by people from places as diverse as what are now Scotland, Germany, England, Turkey, France, Iraq, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Lebanon, Syria, Romania, Spain, Greece, Albania and Italy. All could become Romans and many did.

But if only for the diversitude of their faiths, the medieval Sicilians represented something far more sophisticated, embodied in synagogues, churches and mosques. Sicily reached its cosmopolitan apogee in the first half of the twelfth century. It was not Camelot, but Sicily came closer to that legendary ideal than any other European kingdom of the Middle Ages.

In certain quarters "multicultural," a word whose appearance in the popular lexicon is rather recent, has become a meaningless mantra, a subjective idea that signifies something different in the mind of each person who expresses it. But our paradigm is hardly original. The legal code established by King Roger II in 1140 actually uses the phrase pro varietate populorum, "the diversity of our people."

For all the talk of multiculturalism, or polyculturalism, the concept itself is widely misunderstood, the word too often burdened by a modern political weight it was never meant to bear, dividing us when it should unite us. The term multicultural describes the presence of several distinct cultures in the same society at the same time, with social equality guaranteed to persons of each culture. Sicily's language, traditions and even its cuisine have been shaped by its polyglot heritage. Call it a grand experiment, and call all who share its ideals "Sicilians."

Culture is broadly defined: the beliefs, customs, arts, social practices and other manifestations or intellectual achievements of a particular society, group, place or time, regarded collectively. Understandably, that encompassing definition — and there are others still more encompassing — educes more questions than answers.

When we speak of culture, what do we really mean?

Is culture a way of expressing ourselves, a way of doing things, a mode of thinking or believing? Is it simply art, or cuisine? Is it the music we make or the stories we tell? How many cultures are there? Is there one, or perhaps more than one, for each of us? Is culture identity? Are all cultures equal, and equally worthy of preservation? How do we arrive at culture? Who creates culture, and who propagates it? Who are its keepers, its shapers, its custodians, its defenders? Is culture destiny? Do we define culture, or does it define us? Is culture something to live with, or is it something to be lived? Should culture be loud and arrogant, or silent and humble? Does it shout, or does it whisper? Who "owns" culture? Can there be many cultures within a greater one? How many cultures can exist together peacefully in one place? How does a monoculture divide into subcultures? Who decides what is culture?

Culture, with its nuances and idiosyncrasies, is what makes each of us, and each group of us, different from every other. Were it not for our distinguishing cultures, we would all be the same. Culture is personality. It is humanizing. It touches every one of us. A celebration of cultural diversity is a celebration of ourselves, for to appreciate the culture of others is to enrich our own.

What follows is not an apologia for a specific world view, but a guide to a voyage whose precise course can be charted only by you, the explorer. Perhaps it needs no course. Whatever route you take, yours will be a journey across time, traversing a sea of complexity to reach a crossroads of humanity. The journey is about knowledge and discovery. The points along the way will be at least as meaningful as the destination you arrive at.

Twelfth-century Sicily is a timeless metaphor, for our Arabs, Normans, Byzantines, Jews, Lombards and Germans could just as easily be the peoples of any part of the world. The lessons would be the same. Like so many lessons rooted in human nature and experience, these transcend any single place, defying facile generalities.

Any lessons to be found in these pages will be left to your interpretation. They will be served with only a few morsels of dogmatism — the dogmatism of tolerance. Rigid conclusions are avoided. Pontification has no place in historical narrative, but neither does indifference.

Would that the more elusive lessons had survived the Middle Ages. These pages are part of an effort to revive a few of them as something more than shadows.

Sicily's was a diverse population seeded by successive waves of conquerors, spawning a complex genetic patrimony of diverse haplogroups and a plethora of brown-eyed blondes and blue-eyed brunettes in a place where redheads are still called Normanne (Normans) and raven-haired women More (Moors).

Be it agreed that golden ages are ephemeral by definition, two hundred years is a long time by any measure. Yet our Normans, Fatimids, Swabians and Byzantines would barely be remembered at all were it not for their accomplishments. Normandy today is but a region of France, its dynasties in England and Sicily little more than a faint race memory of heroic conqueror kings. The Fatimid Empire, like that of the Romans, is now a cacophony of disunited nations. Swabia, the cradle of a great dynasty that ruled a Holy Roman Empire, is today an anonymous piece of Germany, while the Byzantines' capital is now a city in Turkey, where the basilica dedicated to Saint Sophia is a museum and the Patriarchate of Constantinople is relegated to a tiny presence.

Like a desert's shifting sands, ethnic identity evolves, its shape ever changing to accommodate continuous influences from within and without. We see only what is left to us, a vestigial trace of something different and perhaps better. But to neglect it altogether is to ignore something of the present.

"Study the past," said Confucius, "if you wish to define the future." History, like science, sometimes teaches us something even when the experiment fails. But Sicily's multicultural experiment was a success for some twenty decades. To describe it requires no hyperbole, no soaring prose, for its barest facts are sufficient to impress the modern mind.

Alas, today's Sicilia is but a shadow of her former incarnation, the Sicilians themselves slightly downtrodden, their island governed from afar for the last five or six centuries, administered since 1946 via a tenuous regional autonomy. There is uncomfortable evidence to suggest that their ancestors were more literate, and perhaps more free, in 1100 than in 1900. By 1300, a radical shift had occurred. For better or worse, the confluence of cultures described in these pages had given way to the largely homogeneous monoculture we see today. But history can be cyclic, and in the present century Sicily has welcomed an influx of new immigrants from around the world.

The annals of medieval history tended to overlook half the population. Sicily bequeaths to us the stories of a few women courageous enough to negotiate treaties, enhearten followers, shelter refugees and run a government while raising families. Their mellifluous names color the chronicles of the Middle Ages: Judith of Evreux, Constance of Hauteville, Elvira of Castile, Margaret of Navarre, Constance of Hohenstaufen. Their modern heirs are the little Tunisian girl who splashes her face with cool water from the Fatimid fountain in Monreale's cloister, and her German sister who places a floppy flower at the tomb of Frederick II in Palermo's cathedral. The spirit of the sisterhood traverses the miles, the languages, the centuries.

Rarely does synergy come easily. Sicily is the world's most conquered island, but only on occasion have the conquests been bloodless. The Byzantine Greeks defeated the Vandals and Goths. The Arabs, in turn, defeated the Byzantines, only to be challenged by the Normans. Later, in an age of pilgrimages and crusades, Messina became a springboard for Europeans en route to their Holy Land, where contested Jerusalem — briefly ruled by a Sicilian king — could boast nearly as much cultural diversity as Palermo.

But for all that, there is much in Sicily for today's visitors to appreciate, and here the flame of the island's past flickers to life. Millions of tourists, students and culture vultures descend upon Sicily each year. For the Greeks, Arabs, Germans, English, French, Albanians, Jews and Spaniards among them, the discovery evokes a feeling of shared affinity with a common heritage. To Germans and Austrians, Frederick was "their" emperor, while the Arabs claim Abdullah al Idrisi as one of their own and the Jews revel in the story of Benjamin of Tudela.

It was here that Swabians befriended Fatimids, and it was here that history witnessed the rare triumph of commonalities over differences.

We should not be surprised. We should be inspired.

CONTENTS

Foreword

Preface

Introduction

Maps

1: Meet the Peoples

2: A Historical Outline

3: Land, Flora, Fauna

4: The Faiths

5. The Vandals and Goths

6. The Byzantine Greeks

7. The Jews

8. The Mikveh of Siracusa

9. The Arabs

10. George Maniakes

11. Christians East and West

12. The Normans

13. Roger I and Judith

14. Roger II and Elvira

15. Abdullah al Idrisi

16. Norman Palace and Genoard

17. Margaret of Navarre

18. Bin Jubayr

19. Joanna of England

20. Benjamin of Tudela

21. Monreale Abbey

22. Thomas Becket and Sicily

23. The Swabians

24. Frederick II

25. Law: Melfi and Maliki

26. The Sicilian Language

27. The Angevins

28. The Aragonese and Castilians

29. The Cuisine

30. Sicilianità, Sicilianistics, Autohistory, Feminism

Afterword

Genealogical Tables

Appendix 1: Timeline

Appendix 2: Reading List

Appendix 3: Places to Visit

Appendix 4: Contrasto

Notes

Sources and Historiography

Acknowledgments

Index

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A number of scholars, readers and friends contributed to this second edition.

Jacqueline Alio, who co-authored with me a scholarly 900-page opus, Kingdom of Sicily 1130-1266, is to be acknowledged for her contributions to the first edition of The Peoples of Sicily. She is known as the biographer of Margaret of Navarre, being the first historian to write that woman's story in full, in any language. Her compendium Queens of Sicily (at 740 pages) and its supplement, Sicilian Queenship, define the field of reginal studies for our royal women before 1266. Many years ago, as a university student, she effected the finest English translation of the Contrasto of Cielo of Alcamo, included here in Appendix 4.

Leonard Chiarelli, the foremost Arabist writing about Sicily, authored the definitive history of the island's Muslims from the pre-Aghlabid era into the Norman period. It was he who first identified the Ibadi community at Kasr'Janni (Enna). Notably, his book A History of Muslim Sicily, first published in 2011 with a revised edition in 2018, considered the phylogeography (genetic haplotypes) of Sicily before many medievalists even knew much at all about that field. Being raised speaking Sicilian as well as English, Leonard can tell you which words spoken among today's Sicilians derive from Arabic without even consulting a reference on the subject.

Professor David Abulafia, CBE, one of the greatest historians of the medieval Mediterranean, read the manuscript of Kingdom of Sicily 1130-1266, from which some material in this book was drawn and for which he very kindly wrote a foreword.

Professor Anne Maltempi, of Kent State University, specializes in the late-medieval and Renaissance era in Sicily. Her insightful article about Sicilian identity in the work of Thomas Fazello, author of Sicily's first printed history, appeared in Mediterranean Studies in 2021. She contributed greatly to the chapter on Sicilianità, the subject of her forthcoming monograph, with its revelations about Sicilian ethnogenesis and nationhood.

Jessica Minieri, who teaches at Binghamton University, has extensively researched the status of women in the "Crown of Aragon," an empire that included the Kingdom of Sicily, with special emphasis on queens held against their will or otherwise exploited by avaricious men. In Sicily this includes young Mary of Aragon, who appears in Table 10 of the genealogical charts.

Professor Virginia Agostinelli offered useful observations about Sicilianistics and its application to studies of medieval and modern history. Monsignor Lorenzo Casati, Orthodox Archbishop of Palermo and the Archdiocese of Italy, offered useful suggestions regarding the historiography and theology of the Great Schism, and Eastern Orthodoxy in general, with insights into the culture and society of the Byzantine Greeks. Allison Scola, who is writing a monograph about the sacred feminine in Sicily, made constructive suggestions regarding perceptions of religion. Many thanks to Karen La Rosa for useful advice on certain details, particularly with regard to wine, and to Conchita Vecchio, John Keahey, Maria Luisa Bongiorno and Salvatore Giardina for their general advice and encouragement.

Information regarding the sale of the pendant of Queen Margaret by Queen Maria Sophia of the Two Sicilies was graciously provided by His Royal Highness Prince Carlo de Bourbon of the Two Sicilies, Duke of Castro, from his family's private archive.

Two gentlemen from the past are worth mentioning. His Eminence Jacques Cardinal Martin (1908-1992) served as Prefect of the Pontifical Household under three popes. An expert in heraldry fluent in half a dozen languages, he administered Vatican diplomatic protocol for decades, and he is credited with developing the international face of the Roman Curia that we see today. He made possible my unrestricted access to the Vatican library and archives. Prince Cyril Toumanoff (1913-1997) was High Historical Consultant of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta and longtime professor of history at Georgetown University, where his students included many budding leaders and at least one future American president. An inveterate Mediterraneanist, he granted me access to the library and archive of the world's oldest order of chivalry, chartered in 1113, by which I was honored to be decorated during the grand mastership of Frà Andrew Bertie.

Over the years, research in original sources has led to a number of discoveries revealed in peer-reviewed articles. Works such as this one could never have been written in Sicily before 1943, or even much before 1960. Indeed, a book quite like it has yet to be written in Italian. The liberation of the island of my ancestors from the yoke of Fascism by Allied forces deserves to be recognized. Many of these heroes are interred at Agira, Catania, Anzio and Nettuno, as well as Arlington and elsewhere, and they are commemorated by an epitaph in Palermo's Anglican church.

© 2014, 2024 Louis A. Mendola